Four times yesterday we were told that Covid numbers are going in the wrong direction.

Cases are up, hospital admissions are up and deaths are up, the grim press conference informed the nation.

Sir Patrick Vallance, the Government’s chief scientific adviser, warned: ‘This is headed in the wrong direction. There’s no cause for complacency here at all.’

Professor Chris Whitty, the chief medical officer, agreed. ‘This is definitely heading the wrong way.’ Some 71 Covid deaths were yesterday recorded across the UK.

A little over six months ago, on March 21 – two days before the nation was plunged into lockdown – exactly the same number of deaths were reported.

The Government is desperate to avoid the virus suddenly running out of control. If cases spike, it could overwhelm the NHS. But all the signs suggest this is not on the cards. Yes, cases are worryingly high. Yes, hospital admissions have doubled in a week. And yes, 71 deaths are a tragedy

The symmetry is chilling and the message from Boris Johnson and his advisers was clear: Follow the rules, toe the line, or we will have no choice but to lock the country down once again. Warning that the nation is at a ‘critical moment’, the PM said: ‘We will not hesitate to take further measures that would, I’m afraid, be more costly than the ones we have put into effect now.’

But although cases and deaths are, indeed, heading up, Britain is in a much better position than it was in the spring. On March 21, when 71 people died of Covid, we were at the start of a rising curve that was about to soar.

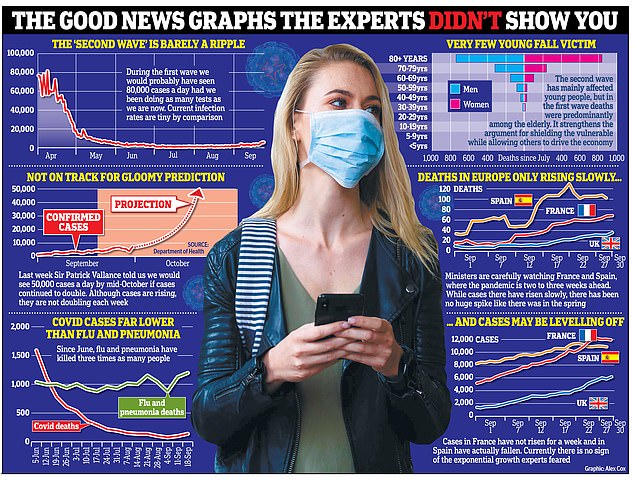

A few days later the daily death toll had hit 1,000. Cases were doubling every three to four days, Professor Whitty reminded us yesterday. The last time he and Sir Patrick appeared together at Downing Street, some ten days ago, they said that cases were doubling every seven days.

Even that now seems like a pessimistic forecast. In reality, the data suggests cases are rising far more slowly, perhaps doubling as slowly as every 21 days.

This may seem like nitpicking, after all, if cases are rising, then so will hospital admissions and deaths will inevitably follow.

Sir Patrick and Professor Whitty often look to France and Spain, which are said to be two to three weeks ahead of the UK in their trajectories. Although both countries have far higher cases than Britain, they have not seen anything like the spike seen in the spring

But the speed of the rise, the gradient of the graph, is crucial when the cost of action to flatten the curve would be so high.

The Government is desperate to avoid the virus suddenly running out of control. If cases spike, it could overwhelm the NHS.

But all the signs suggest this is not on the cards. Yes, cases are worryingly high. Yes, hospital admissions have doubled in a week. And yes, 71 deaths are a tragedy.

But all these figures have been increasing very gradually for a number of weeks.

And a major study by Imperial College London, based on tens of thousands of tests, last night suggested that the rate of growth may even be slowing. It estimated the crucial R rate has dropped to 1.1 – from a peak of roughly 1.5 the week before – suggesting that recent restrictions are working. Exponential growth does not seem imminent.

Sir Patrick and Professor Whitty often look to France and Spain, which are said to be two to three weeks ahead of the UK in their trajectories.

Although both countries have far higher cases than Britain, they have not seen anything like the spike seen in the spring.

Daily cases in both countries stand at about 12,000, if the seven-day rolling average is looked at, which flattens out the peaks and troughs of day-to-day reporting.

This figure has stayed roughly level in France over the past week, and in Spain it has actually dropped slightly. Deaths in both countries are also high – France has about twice Britain’s daily deaths and Spain about triple.

But, again, both have stayed fairly stable in the past fortnight.

Neither country has seen the virus run out of control, as it did in the spring. Much has been made of the 7,000 new coronavirus cases reported in Britain yesterday and the day before.Although these are the highest figures on record, last spring the country was doing only a fraction of the testing, so only a tiny proportion of cases were detected.

If we had been carrying out the same number of tests then, as we are now, we are likely to have seen between 80,000 and 100,000 infections per day.

By that measure what we are currently experiencing is more a ripple than a second wave. The PM is acutely aware of the costs of more restrictions. After a series of bruising headlines about missed cancer screenings during the last shutdown, he was quick to stress last night that the NHS remains open for business.

His officials predict that 74,000 people will die as an indirect result of the spring lockdown – many because they stayed away from hospitals.

Mr Johnson must be sure, before ordering a repeat, that the cure is not worse than the disease.