The World Health Organization has refused to give its blessing to Britain’s plan to space the two doses of Pfizer’s coronavirus vaccine by more than a month.

Officials in the UK have decided to use all available doses of the Pfizer/BioNTech jab, which was the first to be approved, to get a single dose to as many people as possible. In the process they will leave people waiting up to 12 weeks for their second jab.

Covid cases started to fall around 12 days after people got their first dose in studies but, because everyone got a second shot just 10 days later, scientists don’t know how long immunity from the initial jab would last.

The WHO yesterday said governments should be giving people their second dose within 21 to 28 days of having the first, to make sure the vaccine works long-term.

But it did not attack Britain’s decision not to do this, admitting the Government had been forced to make a difficult decision because of spiralling infections and deaths in recent weeks.

One of the experts said they ‘totally acknowledge that countries may see needs to be even more flexible in terms of the administration of the second dose’.

It comes after England’s chief medical officer, Professor Chris Whitty, defended the controversial move again last night, saying the benefits of it outweigh the risks.

He admitted there was a chance it could increase the risk of the virus developing vaccine resistance in the future but that the need to vaccinate people now was overwhelming.

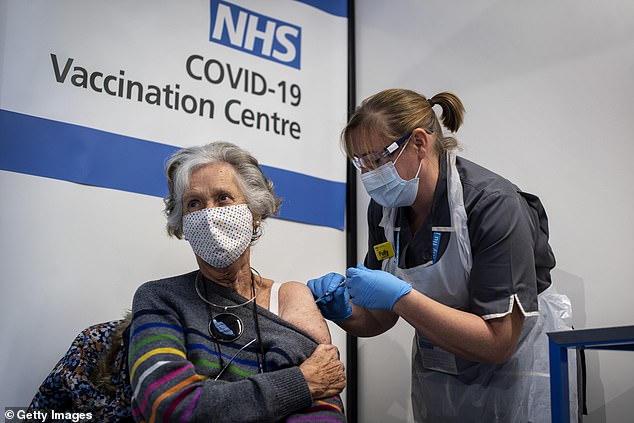

Britain was the first country to start vaccinating members of the public against Covid-19 and has now given jabs to more than 1.3million people, but has had to begin a controversial strategy of stretching the gaps between doses in a bid to protect the elderly from an out-of-control second wave (Pictured: Dr Doreen Brown, 85, gets a vaccine in London)

In a meeting to discuss how doses are spaced out yesterday, WHO experts concluded that, with the Pfizer/BioNTech jab, people should get their second dose 21 to 28 days after the first, with an ‘outer limit’ of six weeks.

This maximum limit is still only half as long as the UK plans to leave it, with hundreds of thousands of people being told they could have to wait three months.

Stockpiles are not big enough for the NHS to proceed with its plan of two doses within a month for every patient, so they’re being stretched to go further until more vaccines are delivered in the spring.

The decision was made by the government’s Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) and endorsed by all of the UK’s chief medical officers.

Dr Alejandro Cravioto, chairman of WHO’s vaccination advisory group, said yesterday: ‘We deliberated and came out with the following recommendation: two doses of this vaccine within 21-28 days.’

His colleague Dr Kate O’Brien said the data being used to justify the 12-week regime being used in the UK was ‘imperfect’.

This meant the WHO was not comfortable officially giving it the seal of approval.

Dr O’Brien said: ‘I think we have to emphasise the need for additional evidence.’

Doctors and scientists were cagey about the UK moving to the spaced-out regimen because of this lack of evidence from clinical trials.

The Pfizer jab was found to prevent 95 per cent of Covid-19 infections in trials when given in two doses three weeks apart, but other schedules weren’t tested.

This means the vaccine could be less effective if it is used differently, and scientists have no way of knowing how much less effective. It is extremely unlikely that spacing the doses would make the jab any less safe.

One GP working in Oxford, Dr Helen Salisbury, said on BBC Radio 4 last week: ‘We really don’t have any data, as far as I’ve been able to ascertain, maybe there’s data they haven’t released – but we don’t have data about immunity after the first dose beyond 21 days when people got their booster in their trial, so we don’t know what happens.’

Although the WHO refused to give its approval to the UK’s 12-week plan, it also did not criticise it.

It said there was a need for flexibility, particularly in countries with bad outbreaks, and that it was up to governments to make their own decision on the balance of risks.

Dr Joachim Hombach said: ‘The [JCVI], the recommending body of the UK, has given more flexibility up to 12 weeks in consideration of the specific circumstances that the country is currently facing.

‘We feel that we need to be grounded in evidence in relation to our recommendations but totally acknowledge that countries may see needs to be even more flexible in terms of administration of the second dose.

‘But it is important to note that there is very little empirical data from the trials that underpin this type of recommendation.’