The morning after an ambulance had rushed me into Derriford Hospital in Plymouth with a dangerously low oxygen level, I was visited by a consultant and his entourage.

He looked at my notes and said: ‘Yes, you definitely have it and you now have two choices – you can stay here in this nice admission ward where you will almost certainly die; or you can be taken down to intensive care (ICU) where we will do all sorts of nasty things to you and you will have a 20 per cent chance of survival.’

This was in mid-March last year and I was one of the first people in the country to develop severe Covid-19 – and certainly one of the first of my age (then 83) to survive.

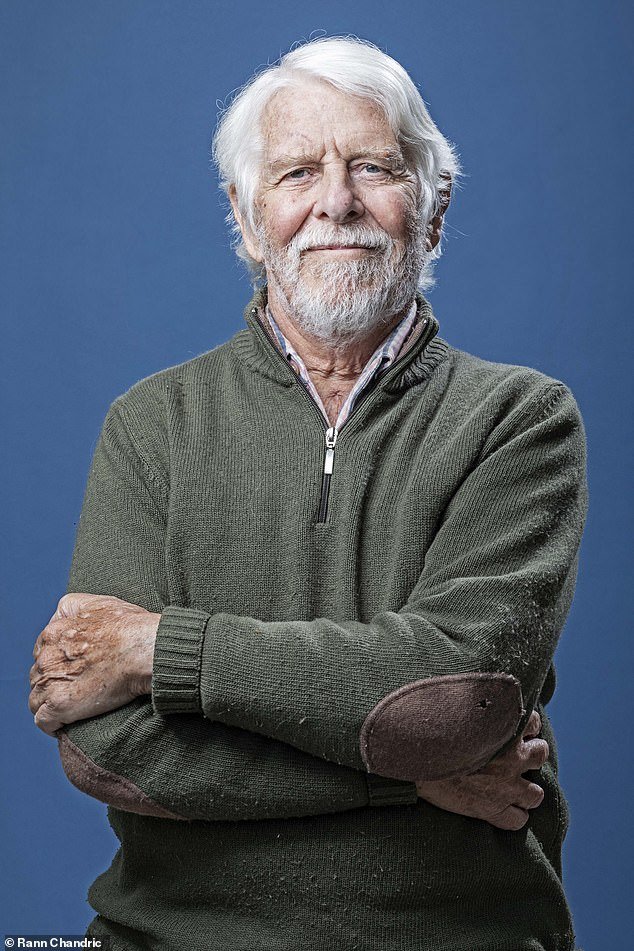

Robin Hanbury-Tenison recalls being one of the first survivors of Covid-19 in the country, after he was rushed to Derriford Hospital in Plymouth with a dangerously low oxygen level in mid-March last year

Now, with my 85th birthday on Friday, I cherish my own life and want to give my wholehearted backing to the Mail’s fundraising appeal for the planned national memorial in St Paul’s Cathedral to those of all ages who didn’t make it.

I know how fortunate I have been.

In ICU I was put into an induced coma for five weeks. During some of this time, I was on a ventilator, had a tracheostomy tube inserted, and was put on kidney dialysis.

My wife, Louella, was told to prepare for the worst three times as I had a less than 5 per cent chance of pulling through – and even if I did, my cognitive ability would probably be severely impaired.

Fortunately, I remember very little of that time. The brain is brilliant at removing memories of pain and indignity, while the drugs I was on triggered all sorts of hallucinations. Towards the end of my time in ICU I began to have some fairly lucid moments and I was able to FaceTime with my family.

I remember seeing their faces as though down a long tube and chatting away intelligently, I thought, as they showed me round our garden and told me they loved me.

But most of the time I was still babbling nonsense and everyone worried about getting me out of my coma.

Then, one day, I was taken to the ‘healing garden’ at Derriford. It is one of the first hospitals in the country to have such a rehab haven for intensive care patients and I was, I believe, only the second patient to use it.

Lying on my bed, with tubes leading in all directions, I was wheeled into the garden and I suddenly felt the sun on my face and was surrounded by flowers.

When I woke up, and despite my tracheostomy tube, I croaked: ‘I think I’m going to live.’ And from then on I started to recover. But it was a slow process.

Seven weeks after being admitted, I was home, but barely able to walk three yards unaided on my Zimmer frame. It is said that it takes a month to recover from each week spent in intensive care, so I set myself the challenge of being able to climb Cornwall’s highest peak, Brown Willy – a modest but steep 1,378ft – by October and attempting to raise £100,000 towards a healing garden for patients in Cornwall’s main hospital at Truro.

Robin went home seven weeks after being admitted and after five weeks in the ICU where he was on a ventilator, and could barely walk three years unaided on his Zimmer frame, but set himself the challenge of being able to climb Cornwall’s highest peak, Brown Willy – a modest but steep 1,378ft – by October (pictured on his climb)

There is no question in my mind that the one in Plymouth saved my life.

In spite of doing the climb on the day of Storm Alex, when Britain endured the highest rainfall since records began, I made it, dragged by Louella and pushed by my son Merlin. And we have raised well over my target now.

I have been extraordinarily lucky, not just to have survived against all the odds, but to be as fit physically and mentally as I was before.

Almost 128,000 people in Britain didn’t make it, through no fault of their own and in spite of the phenomenal efforts made by NHS staff over the past year.

Many more are suffering from Long Covid and will never be fully well again. It is wholly right and appropriate that there should be a national Covid memorial where bereaved families and friends can take comfort in a place where their loved ones can be remembered in peace.

We have all heard heart-breaking stories of those whose lives have been wrecked by this dreadful virus. There is one couple we know who lost the husband to Covid early on and then the wife became very ill. This left their 11-year-old daughter to cope with looking after her baby sibling.

For them, as for so many others, this pandemic has changed everything. The least I feel we can do is help make this memorial a reality – to show that their grief and loss are shared and recognised.

As the Prince of Wales, who is supporting the St Paul’s Cathedral Foundation appeal, has said: ‘This… will help us remember; not just to recall our loss and sorrow, but also to be thankful for everything good that those we have loved brought into our lives.’

Just as we remember those who died in two world wars and all the conflicts since, so we should honour the many who have lost their lives through a pestilence that came from nowhere and wreaked so much havoc for so many.

Robin Hanbury-Tenison is an explorer and author. His latest book is Taming The Four Horsemen, in which he forecast a pandemic.