Whenever a US election delivers a radical change in President, anxieties, even panic, flare in Downing Street about what it will mean for the UK/US relationship.

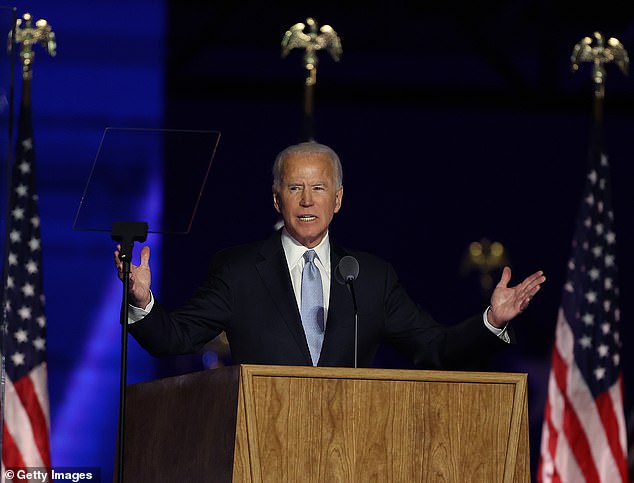

Meanwhile, almost like clockwork, commentators compete to write gloomy obituaries for the ‘Special Relationship’. And this time, following the election of Joe Biden, is no different.

But for goodness sake, everybody, calm down. We have been here before. In 2000, I was Britain’s ambassador in Washington when the result of the US presidential election between the Republican George W. Bush and the Democrat Al Gore hung in the balance.

In the end, after a tense few weeks, the US Supreme Court settled it in Bush’s favour.

The New Labour Downing Street of prime minister Tony Blair had followed the race closely and anxiously. They had a lot of eggs in Gore’s basket. Blair had developed a close personal and political relationship with the previous Democrat president, Bill Clinton.

And so New Labour hoped and prayed that Gore, who had been Clinton’s vice-president, would pick up where Clinton had left off. It was not to be. Bush became president.

Yet despite this, and despite the fact that Blair and Clinton were far closer than Boris Johnson and President Trump, that proved no barrier to Blair developing an equally close relationship with Bush.

Indeed, when I asked one of Bush’s closest advisers whether Blair’s friendship with Clinton would be a problem for the new president, he replied: ‘By your works shall ye be known.’

For ultimately, the notion that Boris Johnson (right) and Donald Trump (left) are politically joined at the hip is rooted in myth – one that seems to be based on Trump’s backing for Brexit and a free trade agreement with the UK

Behind the typically Texan biblical style, there was a profound message: namely that if our national interests coincided, all would be fine.

That was what happened – and there’s no reason to think that, this time round, things will be any different.

For ultimately, the notion that Johnson and Trump are politically joined at the hip is rooted in myth – one that seems to be based on Trump’s backing for Brexit and a free trade agreement with the UK.

Yet this never translated into anything concrete. Though trade negotiations began, Trump has been reluctant to stand up to those in his own country, especially the US agriculture lobby, who were insisting on terms we could never accept.

Meanwhile, in the wider world we have consistently been at loggerheads with Trump’s worldview: his lukewarm support for Nato, his withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal and his withdrawal from the Paris Climate Accord to name but three.

Certainly he was right to criticise the People’s Republic of China for its unfair trade practices, its threats to national security and its assertive expansion of global influence.

But, as our Foreign Office never ceases to say, this is a policy that needs to be handled with care, not in the impulsive and unpredictable way that was a trademark of Trump’s foreign policy.

On the other hand, the raw materials for a close working relationship with President Biden are all there.

After a long career in the US Senate he is extremely well known to us, and to a succession of British ambassadors.

So too are some of his closest foreign policy advisers who can expect high office in his administration, such as President Obama’s national security adviser, Susan Rice, and his deputy secretary of state, Tony Blinken, whom I got to know well some 20 years ago.

Crucially, judging by Biden’s record in the Senate, it is pretty clear that his position on international issues coincides almost exactly with the priorities of British foreign policy.

He will take a firm line with Russia and China. He supports international cooperation.

He will also reset relations with America’s traditional friends and allies in Nato and the European Union, most of whom have been neglected or insulted by Trump.

Even when we are outside the EU, it will be an important British interest that Europe and America enjoy the closest of relations.

And so we must not fall into the trap of thinking this is a zero-sum game. It does not, for example, matter a hoot whether Biden comes to London first before any other European capitals.

In any case he will come to the UK twice next year for the G7 summit and the Paris Climate Accord meeting.

Of course, we still have a lot of work to do explaining Brexit to our American friends, who for decades have supported the idea of European unity without always fully understanding what it entails.

We have been here before. In 2000, I was Britain’s ambassador in Washington when the result of the US presidential election between the Republican George W. Bush and the Democrat Al Gore hung in the balance

But after all, the US is second to none in cherishing its national sovereignty, which is why it is not a member of the International Criminal Court.

So it should well understand the British people’s democratic decision in 2016 to repatriate sovereignty from Brussels.

As for Northern Ireland, it needs to be even more urgently and insistently explained that the British Government will do nothing to damage the Good Friday Agreement.

It is in our interest, above all others, that there should be peace, not violence, in our own nation.

We must never forget that in many areas – from defence and intelligence cooperation to mutual investment – British-American relations have, for decades, been extraordinarily close.

There is absolutely no reason why this should not continue under President Biden. It is so obviously in the national interest of both our countries.