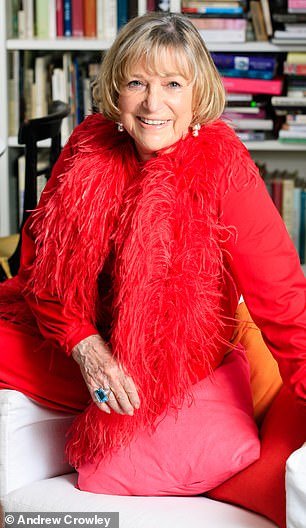

SHIRLEY CONRAN: As someone who is known as ‘Superwoman’, I never dreamt I would want to commit suicide

As someone who is known as ‘Superwoman’, I never dreamt I would want to commit suicide.

I thought only weak-minded people did — not strong-minded people like me. But the night I decided it was easier to start sleeping under a rug on the sofa in the sitting room, rather than make the extra effort to go to bed, should have rung alarm bells.

Even into my late 80s, I’ve never let standards slip. I have even been known to undertake a little light cleaning in the middle of the night, if I had trouble sleeping.

Then, two months after the first lockdown began, having reached rock bottom, I considered taking my life. Humiliated, I was finally forced to seek outside help.

In nearly a year of dealing with social care in Britain, my main, depressing observation is that even private savings count for little in a system that is broken and unfit for purpose.

There is no joined-up thinking between the NHS and Social Services, leaving those who need help most to sink.

If I — a tough, confident businesswoman and former editor — have struggled, I can’t imagine what it’s like for the disadvantaged. Quite simply, it’s a national disgrace.

Our care system was already broken before Covid-19 increased the burden. When you realise that, then you realise the extent and urgency of the problem. Age care requires not only a major funding injection but long-term reform.

Boris Johnson made a pre-election promise that if he won, he would ‘fix’ social care for good (it’s the main reason I voted for him).

Yet the Chancellor’s latest Budget did not once mention the matter. As Mail City editor Alex Brummer commented: ‘What was missing in the Budget? There was absolutely no reference to social care, which is one of the biggest problems facing this country.’

The dreaded virus is not, as some think, an excuse for the Government’s inaction. Successive governments have kicked this can down the road. But I believe this pandemic presents us with a unique opportunity.

As I’ve discovered for myself, the system desperately needs fixing.

Two months before lockdown, in January last year, aged 87, I had an orange-sized tumour removed from my brain and was warned my recovery could take two years.

I paid for a month of convalescent care in a private nursing home. Then I wobbled home happy, supported by my son and two NHS walking sticks.

I prefer to live alone and had adequate home help from a friend for two mornings a week, plus the visiting hospital physiotherapist, who was free. I also paid for a chiropractor for my permanently painful arthritic right knee.

After lockdown, however, all human help was suddenly removed. As I was shielding, no one was allowed inside my flat in Central London. I felt as if my crutches had been ruthlessly yanked away.

As I wrote in the Mail last year, I tried to make the best of it. I read, I wrote, I played Scrabble online. But slowly, in the weeks that followed, I fell apart.

Even eating was stressful — it took me six weeks to get added to a supermarket delivery priority list.

My family have always been exceptionally supportive of me, but my sons were both overworked with coronavirus-related business crises, so I didn’t want to bother them. A neighbour bought me bread and milk, and I relied on my freezer.

Breakfast became instant coffee and a biscuit. So did lunch. In my already weakened body, my energy levels were reduced.

![Pictured: English designer and entrepreneur Terence Conran with his wife Shirley and their baby son Sebastian at home, 1956. Shirley Conran: If I — a tough, confident businesswoman and former editor — have struggled [during the pandemic], I can’t imagine what it’s like for the disadvantaged. Quite simply, it’s a national disgrace](https://i.dailymail.co.uk/1s/2021/03/12/22/40400698-9356967-image-a-86_1615587188728.jpg)

Pictured: English designer and entrepreneur Terence Conran with his wife Shirley and their baby son Sebastian at home, 1956. Shirley Conran: If I — a tough, confident businesswoman and former editor — have struggled [during the pandemic], I can’t imagine what it’s like for the disadvantaged. Quite simply, it’s a national disgrace

I couldn’t spend time with friends or relatives in person but, in any case, I didn’t have enough energy to think or talk. I stopped answering emails and telephone calls.

Sternly, I told myself to keep calm and do my best. But my best wasn’t good enough. By May, I couldn’t concentrate enough to read books, and eventually I had no energy to get to the bathroom.

That’s when the soft, seductive siren voices began to call to my fifth-floor flat: ‘Just . . . jump.’ I had never felt so low in my life. It made me feel guilty and fearful.

Too ashamed to phone either of my sisters, I didn’t want to worry my sons, so I called my beloved, practical ex-daughter-in-law, Georgina, who told me to dial 111 immediately.

Normally, you would call your GP but in those early days of the pandemic I couldn’t get through. Doctors were frantically overworked like everyone else.

What followed was an immensely stressful ordeal that took 22 telephone calls to 111 — one lasted for 40 minutes — to reach the right people. Every time I called, I had to repeat all my details again.

Eventually, I was passed to two departments: NHS Mental Health and my local council’s Social Services. A psychiatrist and a psychologist came to see me.

They spent two hours with me and helped me to understand that my condition was a result of the virus fallout. The lack of human help had affected me physically and this had produced a knock-on effect on my mental health.

Pictured: An elderly woman sitting on the edge of her bed in a nursing home with her head down while a care worker sits close with her for comfort

On top of all that, the 111 calls had been exhausting and infuriating — but a penny had dropped. Pandemic or no pandemic, I was experiencing at first hand the perilous state of elder care in this country. And I was angry.

Since then, the more care I’ve required, the more I’ve realised not only the exorbitant costs (a private care home can be £130,000 a year), but quite how antiquated and confusing the whole healthcare system for the aged is.

These days, I have half an hour of local council care twice a week to shower me, which costs me £1,000 a year. Recently, because of my council’s subcontractor’s incompetence, I was left unwashed for ten days but still had to pay for it.

To be able to walk, I need 20 minutes a week with a private chiropractor, which costs £75 — or £3,900 a year. As I can no longer reach my toenails, my feet are cared for by Jackie from the charity Age UK, who visits me for £22 for half an hour every six weeks, which totals £176 a year.

Many people can’t afford more than £5,000 a year for about an hour-and-a-half of care a week. The cost certainly came as a shock to me.

But if the lockdowns have taught me anything, it’s how valuable human help is to old people — and the fact that your needs can suddenly increase overnight.

Over the course of three lockdowns, I have experienced three relapses (both physical and mental) and two blackouts, requiring ambulance dashes to A&E. I was given MRI scans and sent home, albeit significantly weaker.

I can afford care for my current needs, but I’m bound to require more care in the future and private care costs are eye-watering. Providers can charge £45 an hour to push your wheelchair for a walk.

Boris Johnson made a pre-election promise that if he won, he would ‘fix’ social care for good (it’s the main reason I voted for him),’ writes Conran. Yet the Chancellor’s latest Budget did not once mention the matter. As Mail City editor Alex Brummer commented: ‘What was missing in the Budget? There was absolutely no reference to social care, which is one of the biggest problems facing this country.’

Eventually, I may need permanent live-in care. If so, I might be able to get a private nurse for £650 a week, plus the cost of her food and living expenses — say another weekly £50: that will cost £35,000 a year from my savings.

If I live long enough to get a birthday card from HM The Queen, it might cost me a total of £420,000 [yes, four noughts], not allowing for inflation.

My mother lived to be 97 and I had no trouble paying my share for her delightful care home. But she died 14 years ago, and even a local council care home can now cost from £1,000 a week.

A private care home can cost up to £2,500 a week, which is £130,000 a year [four noughts again]. Few families can afford that, especially as old people live longer if they are well cared for.

NHS healthcare, funded by the taxpayer, involves the treatment, care or aftercare of someone with a disease, illness, injury or disability. Social care is provided by local government — your local council — and is means-tested: it helps with your daily life, such as shopping and washing yourself.

Then you have the postcode lottery. The amount of free care you are entitled to may depend on where you live and your circumstances. You could be charged nothing, or from £20 an hour to provide care in your own home.

The greater use of private-sector providers of home-care service, together with a tendency for street-sharp authorities to charge commercial rates, has increasingly blurred the boundaries between private and public sector.

Since 2010, the State has cut spending on adult social care by £86 million, despite the rapidly increasing demands of an ageing population. According to Age UK, 1.5 million pensioners don’t receive the care and support they need.

Margaret Yeoman, 90, seeing her son John Yeoman, 62, and his wife Denise Yeoman, 63, for the first time in eight weeks as they visit her at the Eothen Homes care home in Whitley Bay, Tyneside in May last year

Just after World War II, the Labour Party started our brilliant NHS. We need equally radical changes now — and this time the money should be spent on Social Services, ensuring that they dovetail efficiently with the NHS.

As our Chancellor is borrowing a great deal of money to get this country up and running again, why doesn’t he borrow a bit more — especially when interest rates are so low, and updating Social Services will undoubtedly provide more jobs.

By 2040, one Briton in four will be over 65 years old and eventually need NHS and local council help.

A person aged 65 can expect to have care costs of about £40,000, on average, over later life, whether or not these costs are met by the council. But there is a lot of variation. Around one person in ten will have care costs of more than £100,000 before accommodation costs, while around one in four will have no costs at all.

The trouble is, we can’t predict which category we — or our parents — will fall into. There is far too much confusion. How do you find out what care you’re entitled to? Where might you go if you are not entitled to anything?

You need to know to ask the right questions. I didn’t realise this until I started to ask persistent, searching questions of my local council and would not be deflected.

It took me weeks, and I still haven’t got all the answers I need.

Who is entitled to state-funded social care? The answer is, not many of us. You are eligible for free social care if you own nothing, have less than £16,000 in savings or if all your possessions are worth less than £23,250. In these days when the average house costs £252,000, this is vanishingly few.

To many, there seems an unfair gap between those who get expensive free care for their parents and those who don’t and so will have to pay for what they can afford.

Whatever the cost of care today, you cannot guess correctly how much it will cost in the future.

Sometimes my dread catches me by surprise at 3am, a time when everything seems bleaker. Now, when that happens, by prior arrangement I phone my eldest son, who is a logical professor. He calms me down and then, he tells me later, spends the rest of the night worrying about his own future and whether he will be a burden on his two sons.

That did it for me. It is the potential burden on my grandchildren, now 30 and 25, that really makes me realise we have to act. I don’t want my grandchildren to feel that their parents are an unfair financial burden. I don’t want my grandchildren to feel impotent or angry. Or indeed suicidal.

Thinking of that makes me want to kick something — or to kick Boris out at the next election. Never mind keeping calm and carrying on, we need to do something.

Every OAP should write to their MP now and demand to be told what he or she is doing to provide adequate age care. We should deluge Boris with real, stamped letters hollering for help.

Pictured: Care home resident Dot Hendy holds her daughter Louise’s hand for the first time since March after Louise successfully passed a Rapid Covid-19 Test immediately before meeting her mother at the King Charles Court Care Home, Falmouth, on November 18, 2020

I propose a long, traffic-stopping wheelchair protest to No. 10, with dodderers angrily waving crutches and teenage grandchildren — good for photo-ops — carrying banners reading ‘AGE CARE OR OUT!’

We might head the protest with some articulate National Treasures of pensionable age: perhaps 74-year-old Felicity Kendal strutting along in silver thigh boots, twirling a baton ahead of a geriatric male brass band; and Joan Collins on the back of a white horse led by the equally indomitable Joanna Lumley, 74. (Remember what Joanna did for the Gurkhas.)

In case you think that’s an unrealistic plan, I did something similar for Women’s Lib — heading a flaming torchlit march from the House of Commons to No. 10, requesting equal pay and equal opportunity. The result was the Equal Pay Act of 1970.

So, Boris, please remember that you yourself will need age care one day — especially for those knees, after all that jogging and cycling you do. Bear in mind that on a Prime Minister’s pension alone, you wouldn’t be able to afford private care.

Don’t think for one moment that we older voters will let you get away with breaking your election promise. Our memories may be failing, but every time we falter or fall — or are left unclean for days — we will remember who is ultimately responsible. You are.

For confidential support, call the Samaritans on 116123 or go to www.samaritans.org.