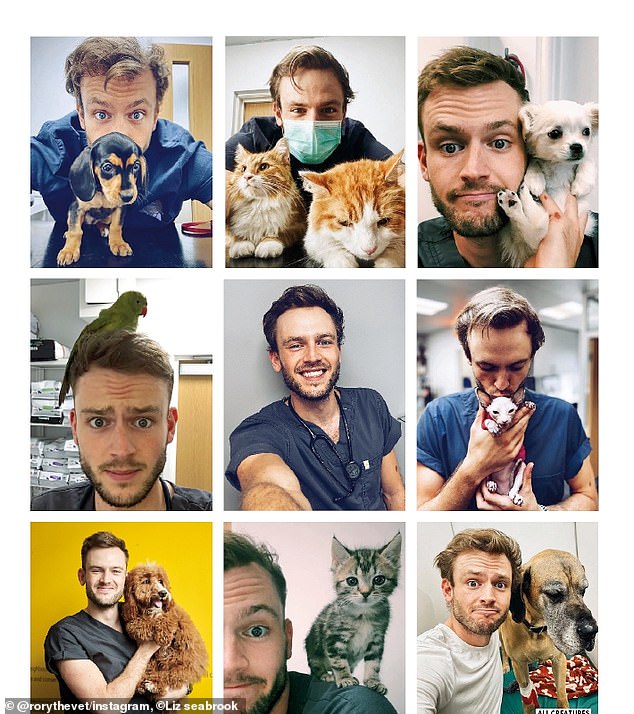

All creatures great, small and cuddly at Rory’s south London surgery

It’s not every vet who admits to falling head over heels for a stray cat, but that’s Rory Cowlam for you. The star of CBBC’s The Pets Factor reveals the highs and heartbreaks of the job – and the day the fur really flew

I knew I wanted to be a vet from the age of four. One of my most vivid memories from childhood is sitting in the car on the way to pick up our new puppy – our great dane Lulu – when she was eight weeks old. We had her until she was ten and she became my best friend and guardian. I used to ride my bicycle into school along with my sister Bethan, my mum and Lulu. If I went out of view, Lulu would grab on to my handlebars and not let go until my mum had caught up. We have had many dogs over the years and I have loved every single one of them, but Lulu and I were kindred spirits.

I was in awe at Lulu’s first vet consult. The vet, Mr Benson, let me listen to her heart through a stethoscope and showed me how to use the weighing scales. As we left, I’d decided. ‘When I grow up, I want to be a vet just like Mr Benson,’

I said. And the rest, as they say, is history.

************

I was a vet by the age of 22, having studied at the Royal Veterinary College. I had a penchant for emergency work and joined a 24-hour veterinary hospital, then a London practice called The Neighbourhood Vet. But I could never have predicted the rollercoaster of emotions and experiences this career path would take me on.

It was at The Neighbourhood Vet practice that, one day, I found myself in theatre and, for the first time, operating on an animal I felt genuine love for. ‘I haven’t felt this much pressure for ever!’ I mumbled to the nurse through my surgical mask. I thought back to the possibly thousands of times I had put scalpel to skin. But this was different. For the first time I was madly in love with the creature lying in front of me.

Rory and his dad with Lulu the Great Dane in 1996

The stray cat had been hit by a car and was brought in by the kind woman who found him. When I first met the little guy, he was curled up with a massive bandage on his badly broken leg. He looked up at me and I looked back at him. His eyes were quite possibly the biggest I had ever seen and I was smitten. I started coming into work half an hour early just to play with the little black cat.

Despite his devilishly handsome face, no owner came forward, and after ten days with us, we had a decision to make. The plan was to amputate his mangled leg then either rehome him to a client of the practice or send him on to Battersea Dogs & Cats Home. But as I cradled him after he woke from the anaesthetic, I knew I just couldn’t let him go.

It took him all of five minutes to settle in to his new home – the flat I shared with Bethan – curling up in a ball on the sofa, as I cooked dinner and tried to think of a name for him. Later, I laughed to myself. ‘There is only one name for a three-legged cat,’ I said to Bethan. ‘Say hello to Tripod.’

**********

Rory with Tripod, the stray cat he adopted

Despite all the joy and the care it takes to heal poorly pets, there is also a darker side to the veterinary profession – the huge psychological toll. Approximately one in four people in the general population will face a mental health issue each year, but early figures suggest higher rates in vets. Almost every vet I speak to has their own negative feelings that they deal with on a regular basis. For me, there was a week back in 2017 that pushed my already fragile, hugely stressed self over the edge into a pit of negativity.

On the Monday, my first patient of the day was an old, skinny cat who was clearly not in a great way. Brought in by a kind couple, the Kims, who had him coming into their garden for a few months, he didn’t have a microchip and no one had responded to their numerous social media posts. The couple announced that they were going to take on ‘Aslan’ for good. And the reason Aslan had gone off his food? His teeth were terrible. I removed 20 of them that day and he went home with his happy new owners.

On Tuesday, a man came in with a cat that was almost completely bald. I could see the animal was so itchy that he had pulled out a huge amount of his fur and was now intent on scratching until he had made himself scabby and sore. I combed through the remaining hair and, just as I expected, found a large amount of flea dirt. I was about to suggest a treatment, but the owner had different plans. ‘I’m afraid I can’t afford your expensive treatments. I think we should put him to sleep,’ he said.

I pleaded, I begged, I offered a discount that would have made my boss blanch. The owner would take none of it, insisting that the fairest thing to do was to end the cat’s life. I simply couldn’t do it.

Graduation day, 2015, with his proud parents and sister Bethan

‘How about you sign your cat over to me so I can keep him here and try to treat him?’ I asked, explaining that it would mean that he lost all rights to ownership of the cat, and that I would be responsible for its care, treatment, cost and finding it a new home. I quickly mocked up a form on the computer and almost threw a pen at him, I was so eager to get him to sign before he changed his mind. I called the cat Scratchy.

On Wednesday, Mr Kim returned. Aslan’s original owner had asked for his cat back. But the Kims had paid for the surgery – and fallen in love with the cat. We agreed that Mr Kim would ask for some financial compensation for the cost of the treatment we carried out on Monday, but I think we both knew it wasn’t the last of it.

Later that day, a man arrived at reception. ‘Are you the vet, pal?’ He was almost spitting the words out. ‘You owe me five hundred quid, mate. You saw my cat on Monday and did a load of expensive tests and stuff that he didn’t need and fleeced the guy who brought him in. Now he wants me to pay because it’s my cat,’ he said. He was edging closer to me as he talked, clenching his fists as if he was going to hit out at any minute. ‘All you vets are the same – charging people stupid money for things they don’t need.’

I felt genuinely threatened. I’d had people accuse me of charging too much – it was part and parcel of being a vet – but I had never been accused of carrying out unnecessary procedures on animals. I told him I only ever did what I thought right for the cat and I suggested he either cover the cost of treatment or allow the Kims to take the cat and give it a loving home.

The man looked me up and down as if I was a crazy person then left. I hated how he had made me feel; how he had made me doubt myself and feel misplaced guilt, as if I had actually done something wrong. After work, I sat in my car, tears dripping down my face. I felt broken and ashamed.

The week got worse. Scratchy’s owner made a formal complaint, saying I had forced him into handing over his cat. How could I be in trouble for trying to do another thing right?

My boss was supportive, but I realised later I had to do something when – trying to take bloods from Scratchy (a tricky task) – I was overwhelmed by frustration and flung the needle at the wall.

I went to see my boss that day and told her I needed a few days off and she very kindly obliged. I was scared that if I continued to work I was going to explode. I went home that evening with a plan: I was going to get therapy, and that was that.

********

I think I shock a lot of people when I tell them that euthanising an animal is often not the worst part of the job. Yes, it’s difficult to end a life, but I am a firm believer that we as vets are incredibly lucky to have euthanasia as a fair option. I think that, if at all possible, children should be taught about the ‘circle of life’ from a young age. There is one particular experience, though, that made me think twice about my stance.

Rupert, the 16-year-old collie cross, had kind eyes and a submissive nature. But you could tell from a mile off that he wasn’t right. He had managed to stand and stumble into the clinic, but only just. He was weak and his kidneys had packed in. It looked as though there was no coming back from this.

I gave him fluids to try to rehydrate him, pain relief and an anti-nausea injection, but we weren’t going to get a miraculous recovery. I called the owner and suggested the family come into the clinic to discuss what we would do. When they arrived, they collapsed to the floor around him, showering him with tears, kisses and love. The children couldn’t have been older than five and seven.

In my job, you deal with the extremes of emotion: utter sadness, sheer aggression, huge disappointment and unadulterated elation. And, in my experience, it’s always the big guys who take the sad times the hardest. There is something devastating in seeing a six-foot man give in to tears over his ill pet. In this case, the father managed to hold back the tears and put an arm around his wife, gave me a nod and ushered the children away from the motionless dog. The daughter followed with one final kiss to her first ever pet, but the son stayed standing.

Great Dane Lupin reminds Rory of his childhood dog and ‘best friend’ Lulu

I watched the ashen face of the young lad, as if he couldn’t quite compute what was happening. When he had got up that morning, he had left for school as normal. Now here he was, in an odd clinical room with Rupert lying on a vet’s bed, and he was being told he had to leave him for ever. He knelt down beside the dog’s head. Have you ever seen a person’s heart break? I am convinced that I did that day. The boy was on his knees next to his best friend and it hit him all at once. His body convulsed as he fell on to the dog and let out a wail that could have woken the dead. His father scooped up his son’s limp form and they left, closing the door behind them. I sat there, tears falling from my chin.

Almost on autopilot I got up, gathered the injection and attached it to Rupert’s intravenous catheter. As I pushed the plunger of the syringe, I stroked him and told him how loved he was. He slipped away peacefully as my own tears pooled on the floor.

The receptionist made me a cup of tea and we sat together in silence for a few minutes. It’s at times like this that I really love our profession and the people I work with. No one said anything. We sat, silently consoling each other. And, just like that, it was back to work, smiling at another client, talking about what to feed her new kitten.

Being a vet is tough but the good outweighs the bad. Being trusted with someone’s pet is a privilege and an honour and something I will never take for granted.

This is an edited extract from The Secret Life of a Vet by Rory Cowlam, which will be published by Coronet on 20 August, price £18.99. The Pets Factor is available on BBC iPlayer